US Attorney General Jeff Sessions is being accused of misleading a Senate hearing about his communications with Russian officials.

We leave to others the debate about whether he misled the committee. But if we were negotiating with Sessions, and he answered our questions in this way, we would have reasons to doubt that he was telling the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth.

Watch this video of Senator Franken’s question, and focus on the body language of Sessions’ response.

First, Sessions averts his eyes from the questioner at the two key moments: as he finishes the sentences “I am not aware of any of those activities” and “I did not have communications with the Russians”.

Second, he seems to stumble over the words “I did not have communications with the Russians”. Arguably, the transcript should have been “I didn’t not have communications with the Russians”!

Third, at the end of his answers, Sessions swallows hard and licks his lips. Swallowing or licking the lips can be signs of a dry mouth; a dry mouth is often a sign of stress or fear; and all but the most pathological of liars find it stressful to lie, mislead or misdirect – particularly under oath. It is said that in ancient China suspected liars were forced to make their statements, then had crushed dry rice put in their mouths. They believed that a truth-teller would have enough saliva to be able to spit the rice out, but a dry-mouthed liar could not. However, this is not a test that can be applied during a Senate hearing or a negotiation, tempting though it would be!

No one of these signals alone would be definitive evidence of deceit. For example, Sessions is at the end of a long day of questioning, so likely has a dry mouth for that reason. Indeed, he swallows in a similar way after some other answers which no-one thinks are misleading.

But this cluster of verbal and non-verbal behaviours should have been noticed by the Senators.

In a negotiation it is valuable to get a sense of when your counterpart is lying, misleading, or holding something back. Participants on our negotiation training courses learn to identify these signals: body language to watch out for, and how to listen for what they say, how they say it, and what they do not say. By seeing videos of their own negotiations, they also learn whether they exhibit these signals or ‘tells’ themselves.

See this interview of Stephen Hartley-Brewer on Sky News for more tips on body language.

Further footage of Sessions’ inauguration hearing can be seen at C-Span.

We will contact you ASAP

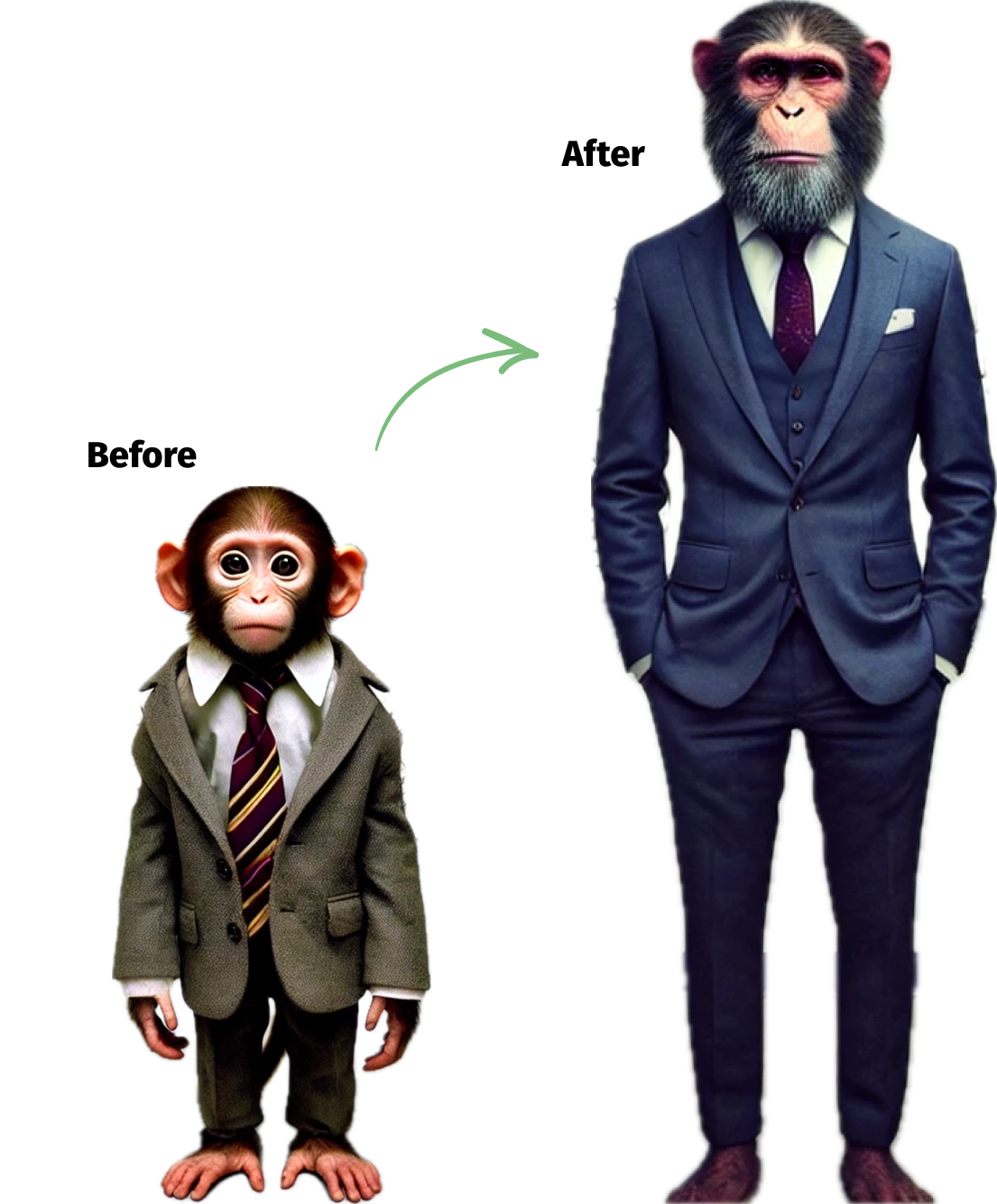

The Monkey is one of the vivid images we use in our training to make a key concept memorable. This image in particular has become a totem for our firm: a toy monkey attends every course, and the BBC made a documentary about us titled The Monkey Man.

A “monkey on your back” is a problem you have – in negotiation terms, that makes you want a deal even on bad terms. E.g. you’re under time pressure / you don’t have any other offers / you think the quality of the other offers is poor.

Monkeys lead most negotiators to underestimate their own relative power and so negotiate too ‘chicken’. And there is a structural reason for this error. – When you look at your own situation you are only too aware of your own monkeys. But the other party may not be aware of these factors.• At the same time, the other guy has problems too – and he isn’t going to tell you about the monkeys on his back as this would only weaken his position. • So you have a distorted view of the power balance. It’s distorted because you have taken account of all your monkeys, but have not allowed for the monkeys he almost certainly has on his back – because you don’t know about those. And the distortion is always in the same direction: it always leads you to underestimate your own power.