At last, an agreement has been reached on Iran’s nuclear programme. But can you remember now many deadlines have been ignored in this long-running saga? Me neither!

The point of a deadline is to put time pressure on your counter-party in a negotiation. “Unless agreement is reached by date N, we will …”

We will what? It seems the answer was “we will carry on negotiating anyway.”

For a deadline to be effective, there have to be negative consequences for the other side. In a commercial negotiation the consequence might be, for example, “we will take up the other offer we have.” For Iran, the consequences of failing to meet a deadline could have been, in extremis, military action.

Given the reluctance of the Western powers to take such action, a more plausible consequence would have been an escalation in the sanctions regime. Ideally, this would take the form of regular (e.g. monthly) and automatic increases in the severity of economic sanctions. The automatic escalation could have been legislated (Obama would probably have faced no opposition from Republican legislators on this) with the stipulation that the auto-ratchet would end if agreement were reached on limiting Iran’s nuclear programme.

It seems that Iran came to the table in the first place only because the existing sanctions regime was hurting badly. Faced with such a ‘deadline with teeth’, the Iranians would have been under real pressure to reach an early agreement. Instead, the willingness of the six powers to ignore their own deadlines could only strengthen the Iranians in their conviction that Obama and his allies were desperate to reach agreement – whether for the President’s legacy or to avoid the potentially de-stabilising consequences of a possible Israeli air-strike on Iran’s nuclear facilities.

Diplomats are supposed to be expert negotiators. But they seem to have spent years repeating the same arguments to each other. Instead of falling into ‘the argument trap’, they would have done better to use both creativity and power to bring these important negotiations to an earlier conclusion.

We will contact you ASAP

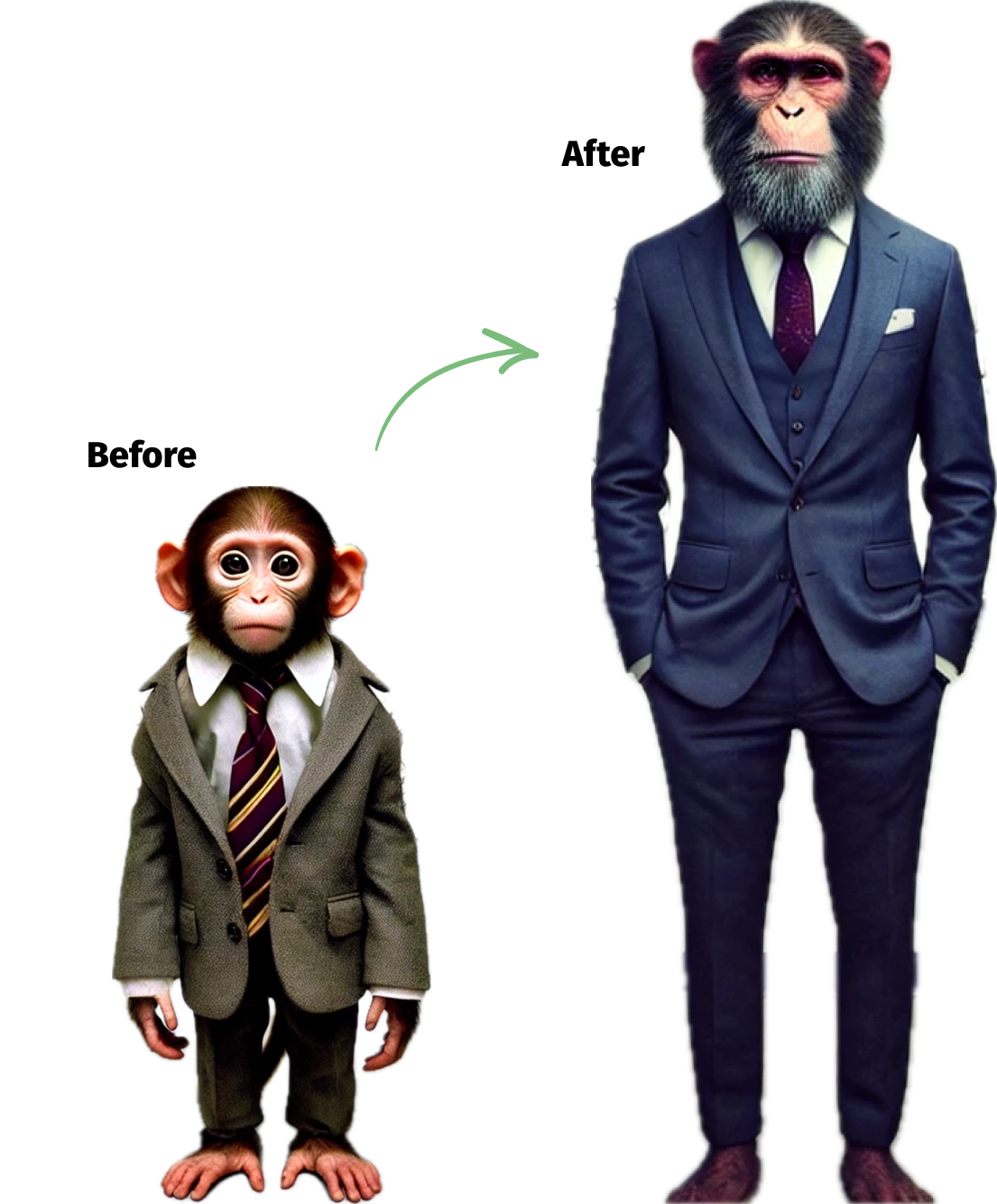

The Monkey is one of the vivid images we use in our training to make a key concept memorable. This image in particular has become a totem for our firm: a toy monkey attends every course, and the BBC made a documentary about us titled The Monkey Man.

A “monkey on your back” is a problem you have – in negotiation terms, that makes you want a deal even on bad terms. E.g. you’re under time pressure / you don’t have any other offers / you think the quality of the other offers is poor.

Monkeys lead most negotiators to underestimate their own relative power and so negotiate too ‘chicken’. And there is a structural reason for this error. – When you look at your own situation you are only too aware of your own monkeys. But the other party may not be aware of these factors.• At the same time, the other guy has problems too – and he isn’t going to tell you about the monkeys on his back as this would only weaken his position. • So you have a distorted view of the power balance. It’s distorted because you have taken account of all your monkeys, but have not allowed for the monkeys he almost certainly has on his back – because you don’t know about those. And the distortion is always in the same direction: it always leads you to underestimate your own power.