The Financial Times has published an excellent article about M&A fees which includes some great charts of deal-by-deal fee rates.

Huge variation in fees paid for M&A advice: negotiation matters! (copyright FT)

What leaps out from the scatter plots is the vast range between high and low fees even for similar-sized deals. It proves that there is vast scope for negotiating M&A fees, with millions or tens of millions to be bargained over.

Partly by applying skills and tactics valuable in any negotiation, including:

And partly by being smarter about the fee structures you use. The article mentions several structures, including ‘discretionary’ fees and ‘ratchets’. The difference between a very low and very high fee often depends on whether a bank gets paid the discretionary fee it hoped, or achieves a deal at which the ‘ratchet’ pays out.

When we train bankers to negotiate M&A fees we help them avoid the pitfalls of each structure.

A bank takes three risks when offering a discretionary fee instead of a contractual one.

Bankers agreeing discretionary fees: are you thinking clearly about these risks? Why is the client asking for discretionary fees? What smart questions can you ask, and what structures can you use, to mitigate the risks of going unpaid, and to maximise your chances of a big payday?

Most bankers fall into the ‘estate agent’ trap. Which is ironic, given that estate agents might be the only profession lower in the public’s esteem than banking! You pitch to sell a flat / company which you think is likely to sell for €1 million / billion. You feel you need to tell the seller that you can sell their flat / company for a very punchy €1.2 million / billion, because you think that will get you selected as agent / banker. But then you raise the topic of a ratchet, above which you’ll get paid big bucks, and the client says “you said you could sell it for €1.2 – so the ratchet needs to pay out only above €1.2”. Trapped!

Here is a (rare) piece of free advice. Don’t behave like a shiny-suited estate agent when you’re trying to portray yourself as an urbane master of finance.

We help bankers play the many angles of ratchet negotiations. How can we get a feel for the seller’s true opinion on what their company is worth? What if the seller has unrealistic expectations? What if the markets turn down during the deal process? What if the company’s EBITDA is actually lower than they told us before we set the trigger level? What if the client does not take its highest bid, because it cares about non-price items?

Hartley-Brewer Negotiation Consultants are the acknowledged experts in investment banking negotiation, including fees. With our help, your fee negotiations with your clients will demonstrate the creativity, collaboration, intelligence and firmness that you will deploy when negotiating for them.

Note on the charts: the Financial Times’ data, from Dealogic, are for sellside M&A advice to US public companies, 2014-2016. The FT does not clearly state whether these deals all completed: non-completion might account for the ‘zero’ fees in the charts.

We will contact you ASAP

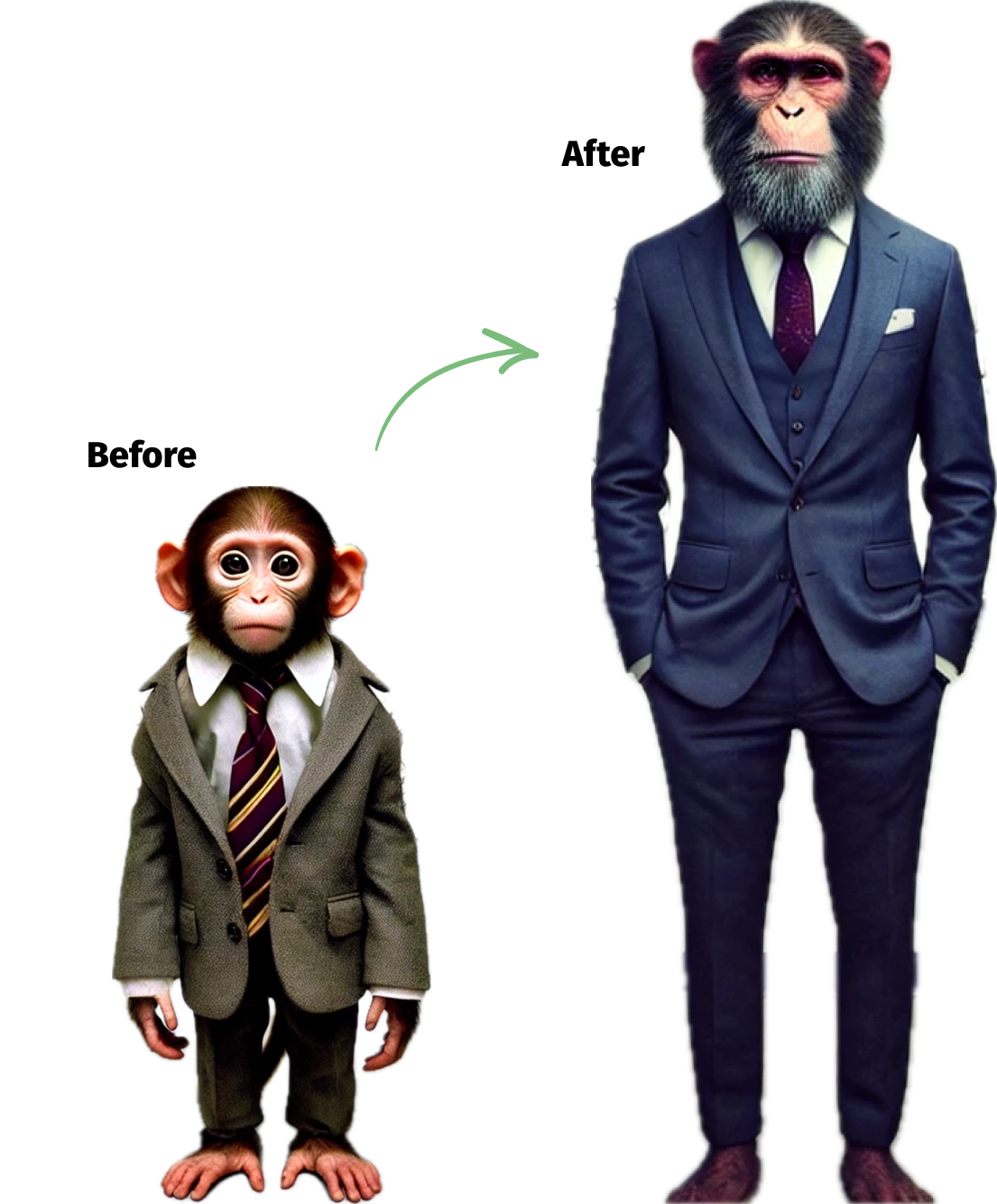

The Monkey is one of the vivid images we use in our training to make a key concept memorable. This image in particular has become a totem for our firm: a toy monkey attends every course, and the BBC made a documentary about us titled The Monkey Man.

A “monkey on your back” is a problem you have – in negotiation terms, that makes you want a deal even on bad terms. E.g. you’re under time pressure / you don’t have any other offers / you think the quality of the other offers is poor.

Monkeys lead most negotiators to underestimate their own relative power and so negotiate too ‘chicken’. And there is a structural reason for this error. – When you look at your own situation you are only too aware of your own monkeys. But the other party may not be aware of these factors.• At the same time, the other guy has problems too – and he isn’t going to tell you about the monkeys on his back as this would only weaken his position. • So you have a distorted view of the power balance. It’s distorted because you have taken account of all your monkeys, but have not allowed for the monkeys he almost certainly has on his back – because you don’t know about those. And the distortion is always in the same direction: it always leads you to underestimate your own power.