Back in the 1990s the Independent wrote a feature on our negotiation training course.

Some things have changed: we can no longer persuade clients that four days is the right amount of time to devote to mastering negotiation skills, and inflation has had its way with our fees. But the monkey is still a highlight, and our senior clients still find that they have a lot to learn – a point one banker makes more bluntly in the article!

Teaching bankers how to negotiate deals is not as easy as it sounds. David Cohen meets a man who is paid pounds 3,750 a day to get results

DAVID COHEN Wednesday 29 July 1992

IN A suite high above the City, a man with a monkey on his back bears down on six men in pinstripe suits, cringing behind cardboard name tags. He dangles the monkey – a toy, of course – inches from the faces peeping over the Armani ties and lets loose a stream of criticism. He then breaks into a waltz with his primate partner. The monkey belongs to Mike Hartley-Brewer, reputedly the highest paid coach in the City. For a cool pounds 3,750 a day, he trains top executives in the art of negotiation. It is the first afternoon of an intensive four-day course at a merchant bank, and Mr Hartley- Brewer, 48, is illustrating, in somewhat bizarre fashion, the finer points of his craft.

‘A negotiation is like a waltz,’ he booms. ‘Unless it is skilfully led, you stand on each other’s toes. You want to glide through each movement, past the curtain and on to the ‘balcony of agreement’, where you can consummate the relationship.’

This week his ‘victims’ are six merchant bankers dispatched by their employer (who wants to remain nameless) to sharpen their negotiating skills. Outside the training room at the Barbican, these directors and assistant directors are the professionals on whose wisdom blue-chip clients such as ICI and Hanson rely. They are the laptop-toting elite, the veterans of the multi-million-pound deal, the ‘big swinging d*cks’ who strut around the City charging seven-figure fees for their advice.

For them, training is a relatively new experience, something they once thought that only callow Oxbridge recruits well down the corporate ladder might require. As one confided: ‘Almost everything we do – from friendly takeovers to agreeing the rates on loan agreements – involves protracted negotiations. This is our territory, so until recently the idea that a banker could be taught to negotiate was like asking grandma to suck eggs. It was just assumed that if you were bright enough to reach director of this bank, you knew how to negotiate.’

Today, after the first videotaped role- play and much robust fun and good humour, the bankers are discovering what amateur negotiators they really are.

‘You wimp,’ says Mr Hartley-Brewer, taunting Martin, one of the bankers. ‘You gave away the store!’ Martin is having his performance dissected while the rest of the class sit back and enjoy the spectacle.

‘But my negotiating position was weak,’ pleads Martin.

‘Yes,’ counters Mr Hartley-Brewer, ‘but so was his. When you negotiate, you take all your secret problems in with you – stuff like ‘the chairman will shoot me if I don’t get their business’. These are your ‘monkeys’ and you never come to the table without them. So why, just because you can’t see them, do you assume the other guy hasn’t got any? Always adjust your power meter for the unknown monkeys crawling on the other guy’s back.’

To Martin’s relief, Mr Hartley-Brewer turns to his opponent in the role play, Stephen. Flushed with the success of a favourable deal, Stephen is beginning to feel some immunity. ‘Don’t be floppy!’ Mr Hartley-Brewer bellows. He tells the group that there are ‘floppy’ phrases (such as ‘I, uh, was hoping for something in the range of, uh . . . ‘) and floppy body language (such as the infamous ‘bum wriggle’). Translated, these undermined Stephen’s power by sending signals that he was not committed to his position.

Mr Hartley-Brewer’s former career as an adviser to the Callaghan government and, later, as troubleshooter for an international oil trading company taught him that the outcome of a negotiation often has little to do with the merits of the arguments. Instead, negotiations are largely about power.

Simply put, there are two types of negotiating strategies – ‘win-lose’ and ‘win-win’. In ‘win-lose’, there is a fixed cake and the two sides are down to bargaining over who gets a bigger slice. It becomes a competitive power game. In ‘win-win’, however, there is an attempt to focus on interests, to look for creative ways of sweetening the deal for both sides. The climate is co-operative rather than conflictual.

‘The real world,’ Mr Hartley-Brewer says, ‘is a mixed game, so you’ve got to be prepared to use both strategies appropriately. Most people have a great fear of failure, so their instinctive response is to mistrust the other side. Then they get locked into issues of face and lose sight of what they’re really trying to achieve. My job is to get them rock-solid on the power plays and then, with the confidence installed, get them to tease out the best deal for both sides.’

His views are shared by his partner, Andrew Gottschalk, who was London Business School’s negotiating expert when they met 10 years ago. In 1985 they formed a partnership, and the resulting mix of the streetwise and the sophisticated proved not only dynamic, but highly lucrative. The clientele of their pounds 500,000- a-year, two-man consultancy includes some of the biggest hitters in the City.

But is it necessary to be so tough on the bankers? ‘They live in the jungle so they can look after themselves,’ says Mr Hartley-Brewer. ‘Merchant bankers tend to be highly intelligent and self-confident, even a touch arrogant. It makes no impact if you pussy-foot. They want it fast and straight.’

The training aims to strike a balance between competitive and co-operative ways of negotiating. But by day three, after 20 hours of coaching and role plays, the bankers are still some way from getting the balance right. Mr Hartley-Brewer has split them into two teams. One, led by Hamilton, has come to discuss a friendly takeover of Stephen’s company. After an hour, the negotiation is hopelessly stalled, with the two sides miles apart and the atmosphere cooling by the second.

Partly, personalities are to blame. Hamilton is what the Hartley-Brewer handbook calls a ‘numbers’ type. Committed to the logic of his bid, he dogmatically explains why his number is correct and, when you don’t agree, he explains it again . . . slowly. Stephen, on the other hand, who displays all the sensitivity of a debt collector, is a ‘tough’. He thrives on continued aggression and inflexibility. By holding up their errors to ridicule, Mr Hartley-Brewer is provoking self-awareness so they can better manage their behaviour.

With only one day of the course remaining and a ‘breakdown’ in talks imminent, Mr Hartley-Brewer is becoming anxious. On another seminar, the bankers’ colleagues botched the same deal and failed to wrap it up by the time the course closed. As one recalls: ‘I thought I was the creative, conciliatory type, but the course showed that I was over-analytical and argumentative. As someone who prides himself on his intellect, I was devastated by my inability to get it right. I felt like I’d been shown up. To work 10 years in the City and to see you’ve learnt f**k-all is a humbling experience.’

Despite additional pointers by their teacher, the pros have once again – to borrow merchant banking jargon – ‘come up smelling of dog’s balls’.

Mr Hartley-Brewer calls for a break. ‘Take a cooler and look where you’re going wrong,’ he says. ‘You’re head-banging, point-scoring and making sarcastic comments – just about everything on the ‘behaviour dont’s’ list. Remember the law of holes – when you’re in one, stop digging! And what’s happened to the ‘information exchange’? How can you make a deal if neither of you will tell the other side what you really want?’

The negotiators go home for the night, considering their failure. ‘I have seen what in my heart of hearts I expected to see, though not what I wanted to see,’ says Stephen ruefully. ‘I hoped to be more fluent and more reasonable – less of a ‘tough’, I suppose. I’m realising that’s it’s not about changing who I am though, but rather understanding the pitfalls of my style and managing my behaviour to best effect.’

The next morning, after quick team conferences, they resume talks. The camera whirrs and suddenly there is progress. It isn’t a particularly graceful waltz, but at least the dancers have stopped kicking each other’s ankles.

‘All very well,’ says one, ‘but what happens if I come up against another Hartley-Brewer negotiator? Will we recognise each other? Will our skills be neutralised?’

‘You might recognise each other,’ says Mr Hartley-Brewer, ‘and if you do, you’ll know that neither of you can be ripped off. So you’ll work together to build a deal that satisfies you both. And you’ll get there with the minimum of fencing and posturing.’

By the final afternoon, however, it all clicks into place. The bankers race through the final role-play and shake hands on a win-win deal with hardly an insult traded. ‘It was brisk, it was businesslike, it was smooth as could be,’ beams Mr Hartley-Brewer, two-stepping across the floor, his monkey lying forgotten on the table. ‘It’s so simple – when you want to make love, when you work the steps of the dance and manage your behaviour, a deal becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy.’

We will contact you ASAP

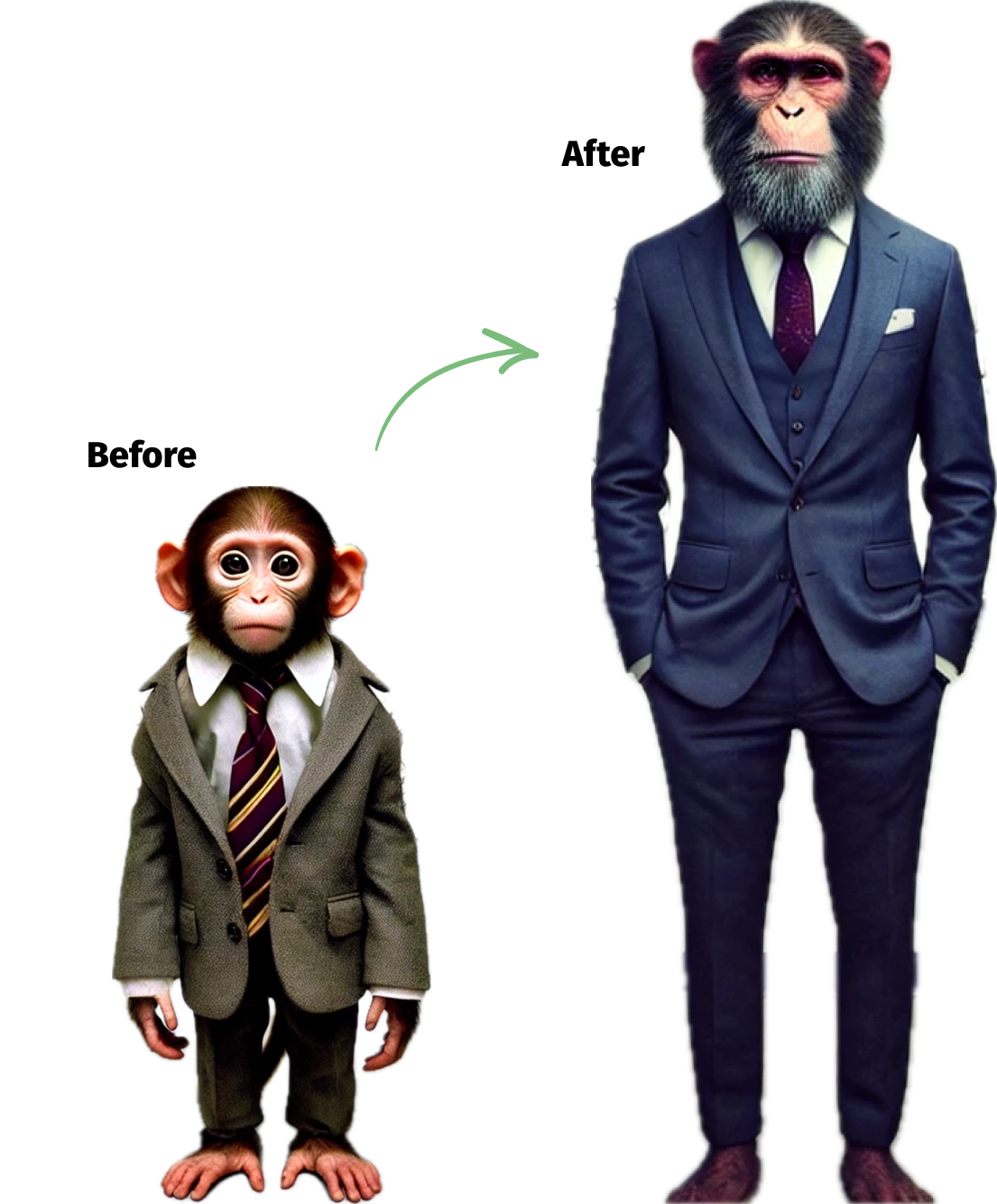

The Monkey is one of the vivid images we use in our training to make a key concept memorable. This image in particular has become a totem for our firm: a toy monkey attends every course, and the BBC made a documentary about us titled The Monkey Man.

A “monkey on your back” is a problem you have – in negotiation terms, that makes you want a deal even on bad terms. E.g. you’re under time pressure / you don’t have any other offers / you think the quality of the other offers is poor.

Monkeys lead most negotiators to underestimate their own relative power and so negotiate too ‘chicken’. And there is a structural reason for this error. – When you look at your own situation you are only too aware of your own monkeys. But the other party may not be aware of these factors.• At the same time, the other guy has problems too – and he isn’t going to tell you about the monkeys on his back as this would only weaken his position. • So you have a distorted view of the power balance. It’s distorted because you have taken account of all your monkeys, but have not allowed for the monkeys he almost certainly has on his back – because you don’t know about those. And the distortion is always in the same direction: it always leads you to underestimate your own power.